CKBlog: The Market

Friday, March 07, 2025

Tariffs and Markets

by The CastleKeep Team

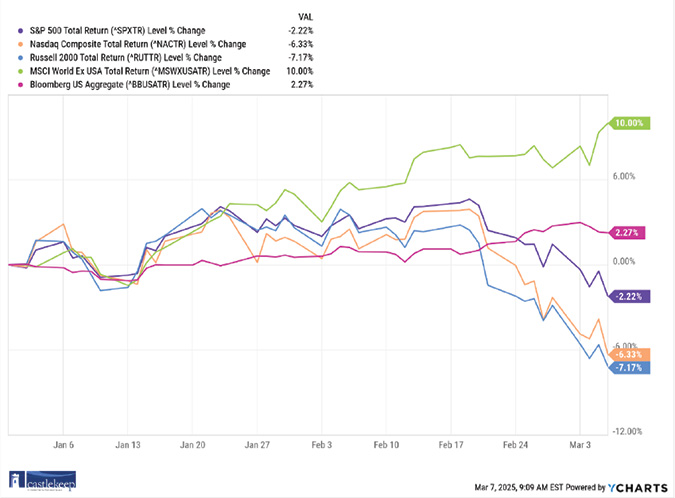

Let us begin by addressing the stock and bond markets. As we write this, the S&P 500 Index is down more than 2% on the year and roughly 6% from its all-time high in late January.

Technology companies have been hit worse, with the tech-heavy NASDAQ Composite down more than 6% on the year and more than 10% from its all-time high in December 2024. Nvidia, as an example, is down roughly 25% from its January high through March 6, 2025 (but still up 25% over the past twelve months).

Smaller companies, as represented by the Russell 2000 Index, are down more than 7% on the year and roughly 15% from the highs experienced in November 2024.

But it is not all bad news for diversified portfolios. Bonds have rallied this year with the Bloomberg US Aggregate Total Return Bond Index up more than 2% including interest.

International equity markets have been strong, with the MSCI World Excluding US Index up more than 9% year-to-date. The graph below reflects the total returns of these indexes:

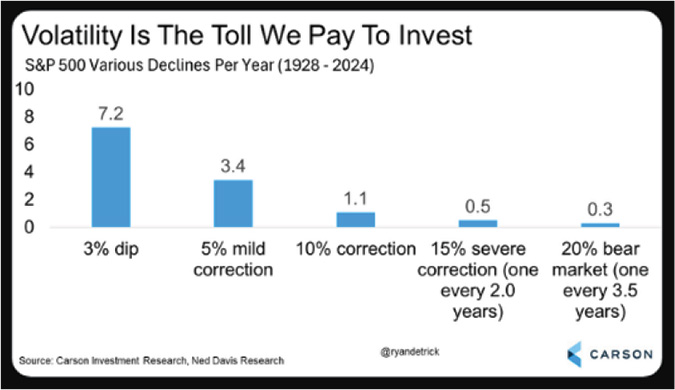

While sell-offs like the one we are currently experiencing can feel painful, it is important to remember that they are also normal. In fact, from 1928 through 2024, a 5% or greater drop for the S&P 500 Index happened on average 3.4 times per year. The chart below from Carson Investment Research shows the average number of times the S&P 500 experienced a downturn by order of magnitude:

Last year, the S&P 500 experienced two declines of 5% or more but ended the year with a total return of 25%. Five percent drawdowns are more normal than you might think and have occurred even in the strongest of years.

Can it get worse? Absolutely. But that also would not be out of the ordinary. Since 1928, the S&P 500 averaged more than one correction of 10% or more per year.

Sell-offs are not unusual. What causes the sell-off varies, but periods of drawdowns are the price we pay for the returns that stocks have delivered for the last 100+ years.

Tariffs

We can debate the cause of this latest sell-off. The reality is that the market was due for a cooling-off period regardless of the catalyst. Even the greatest of athletes need breaks from time to time.

But suppose the pundits on TV are correct that the recent turbulence can be ascribed mainly to tariff talk. Let’s review the basics of tariffs and how they may impact the economy and markets from a politically neutral standpoint.

Definition from the Oxford Dictionary:

tariff: (n) a tax or duty to be paid on a particular class of imports or exports.

Importantly, tariffs are paid by the importer and paid to the government that imposed the levy. The objective of tariffs has historically been to raise revenues for the government and/or to protect domestic markets or goods.

The first evidence of a tariff was in Ancient Greece where the port of Piraeus in Athens enforced levies to raise taxes for the government. In the 1300s, King Edward III began using tariffs to protect the domestic wool market in Great Britain. The United States instituted its first tariff in 1789.

In fact, tariffs were the primary funding tool for the US Government until the establishment of the permanent income tax in the early 1900s. Governments around the world have been using tariffs for over 2,000 years.

If you have ever lived abroad, you likely have experienced hefty tariffs first-hand. Our founder and CIO, Charlie Haberstroh, lived in Brazil in the 1980s. During that time, Brazil levied a 100% tariff on foreign made cars imported into Brazil. If Charlie wanted to purchase a $10,000 Chevy from the USA he certainly could. However, as soon as that Chevy arrived at the Brazilian border, he (or the agent that imported the vehicle) would have paid an additional $10,000 for the tariff. That Chevy would have cost him $20,000 ($10,000 to Chevrolet and $10,000 to the Brazilian Government). As a result, and as much as he loved American made cars, he only purchased cars made in Brazil during his time in São Paulo.

So what does this all mean for our economy and markets today?

First, this is a dynamic situation. In the time it took us to write this, the Trump administration announced a pause on certain Mexican imports and that talks were ongoing to do the same with Canada. President Trump then signed an Executive Order excluding items included in the USMCA Trade Agreement which he signed into law near the end of his first term in 2020.

You may have heard of the quote “the only thing certain in life is uncertainty ... “

We believe that for certain perishable goods, prices will likely increase by the tariff amount in the short-term. Take Mexican avocados at the previously proposed (for now?) 25% tariff as an example. Under this example, the truck load of avocados that is currently en route to the border would be hit by a 25% tariff upon arrival (if proposed tariffs remain in place).

That doesn’t mean avocados from Mexico will always be 25% more expensive than they were just days ago. For one, they are perishable goods so there is only a finite period where consumers are willing to buy that particular harvest. Harvested avocados will ripen and become obsolete if not sold and consumed. Producers will likely adjust their prices quickly to react to demand. At $1, we may buy that Mexican avocado. At $1.25, we might think twice. Chipotle Restaurants will likely not balk at tomorrow’s shipment, but you better believe they are already negotiating with their suppliers on next week’s delivery. Prices are dynamic for most goods, especially those that perish. Mexican producers may be forced to lower prices if the 25% tariff results in less demand from American consumers.

For non-perishable goods, like autos, it may take more time, but prices will likely adjust as well. Suppose for the sake of argument, Ford manufactures its F-150 trucks exclusively in Mexico and Chevy produces its Silverado trucks exclusively in the US. Next week’s delivery of Mexican made Ford F-150s may be hit with 25% tariffs when they arrive at the US border. But will consumers pay 25% more for that same truck? Or will Ford and its dealers offset the tariff with incentives to entice their customers to stick with Ford?

If Ford doesn’t provide incentives, might a previously loyal Ford customer waltz into the Chevy dealer next door if the cost of their beloved F-150 just went from $80,000 to $100,000 and the Silverado’s price remains unchanged?

If the tariffs stick, might Ford re-shuffle its production and re-establish manufacturing plants in the US to avoid the tariffs? It certainly would take time and require significant capital expenditures, but it may be worth the effort in the long run. Just as it made sense for US auto makers to move manufacturing to Mexico over the last several decades to take advantage of cheaper labor and trade deals …

Currency fluctuations are also a factor and too complex to analyze in this post. But during the previous Trump Administration, a stronger US dollar helped offset the costs of tariffs on Chinese made goods imported to the US.

We hope you now have a better idea as to why markets have been so volatile. The notion of tariffs is complex and can certainly be difficult to grasp.

What Now?

The current tariff talk (and action) is disruptive. But we’ve been here before. Not only was this a focus during President Trump’s first term (the original tariffs on Chinese goods remained in place during the Biden Administration and were recently just increased by President Trump), but countries as well as corporations have been dealing with tariffs for over 2,000 years.

Consumers will react. Companies will adapt. Politicians will come and go.

The stock and bond markets have been adjusting, too. This can trigger panic, but it also presents opportunities. While our investment team will practice patience, we may act if we believe it is prudent to do so. Just as we did during previous dynamic market events.

Some events such as the dot-com bubble, the Global Financial Crisis, and Covid all resulted in serious (yet temporary) pain. Others were not as material for markets, with Trump Tariffs 1.0 being an example.

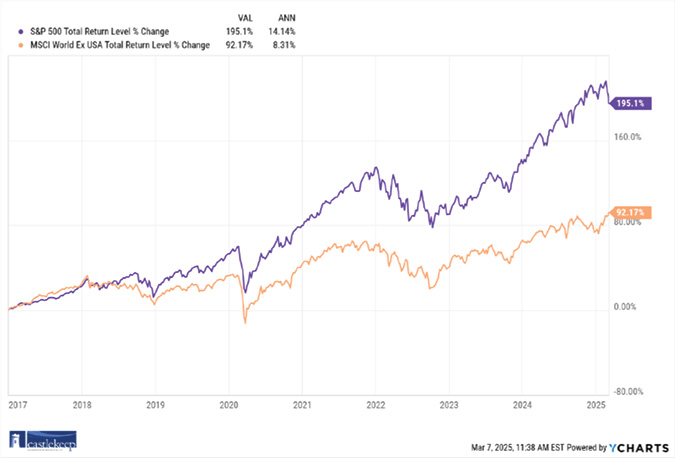

Can you spot the sell-off relating to tariffs the first time around on the following graph of the S&P 500 and MSCI World Excluding US Indexes since 2017? The first of several tariffs on Chinese goods went into effect in the first quarter of 2018. Should we have materially lowered exposure to stocks then (with the benefit of hindsight of course)?

Might this round of tariff anxiety play out in a similar way? Short-term concern but with capitalism prevailing?

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. We might be in the beginning stages of a dramatic sell-off. We also might not be. Which is precisely why we remain patient and diversified. We would encourage investors to maintain a similar mindset. Not easy, but over time it has been the winning approach.

If you would like to discuss the current environment and how it may impact investments, please reach out. As we have written and said before, the best part of our day is when we interact with you.

Sincerely,

The CastleKeep Team

Download Tariffs and Markets (PDF)