CKBlog: Financial Planning

Monday, December 15, 2025

Tax Strategies for Concentrated Positions

by Steve Haberstroh, Partner

Reduce Concentration While Finding Comfort

Your company stock has soared. The shares you own are now the majority of your net worth.You are concerned that you are taking on too much risk with exposure to a single stock, but you’ve also calculated the long-term capital gains tax due if you sold shares. You feel paralyzed.

You bought shares of several of the technology behemoths more than five years ago. The stock prices have increased so much (which is ultimately a good thing), however, the day-to-day price swings are causing you anxiety. The moves, after all, materially impact your future financial plans. You feel as though you should sell some shares to diversify but your cost basis is so low that your net worth on paper will dramatically change after paying Uncle Sam’s capital gains tax. You feel paralyzed.

You are not alone.

The two scenarios above, and endless variations of the same, are becoming more common place. In this post we will examine the ways in which clients can potentially sell down or diversify low-basis, concentrated positions without triggering capital gains taxes that might put a wrench in your financial plans.

First, a very important disclaimer.This note should not be construed as specific financial advice. Each person’s situation is unique. It is imperative that you consult with your advisors to develop a sound plan that meets your objectives. This also should not be construed as tax advice. CastleKeep as a firm nor any of its partners or employees are CPAs. We encourage you to consult with your tax professional before making any changes to your financial plan.

Tax Loss Harvesting

A common approach to tax planning, tax loss harvesting, involves selling individual holdings that have unrealized losses and substituting the position with an investment that has reasonable expectations to produce a similar return as the position sold at a loss.

A classic example of tax loss harvesting is substituting Pepsi stock for Coca Cola stock. While not identical companies, you could make the case that the businesses, and therefore stock price, of the beverage giants might act in a similar fashion.

Let’s assume you bought $100,000 worth of shares in Coca Cola. After a spate of bad news for the company, your position is now worth $80,000. You could sell shares of Coke, realize a $20,000 loss for tax purposes and purchase $80,000 in Pepsi stock. Your exposure to the global beverage and snack food sector didn’t change, but you were able to “harvest” a $20,000 loss that can be used to offset an equal capital gain from other areas of your portfolio.

Note: The IRS mandates you hold the new position for at least 30 days to avoid the so called “wash sale rule” (for more information on this rule, see: Schwab’s Primer on Wash Sales).

Strategy in Practice: Tax loss harvesting is a relatively simple process that can be completed each year (assuming not every one of your stocks always go up!) In the example above, you sold Coca Cola and realized a loss of $20,000. You could then sell sufficient shares of your concentrated position to match that loss with a $20,000 gain. If matched equally, there would be no capital gains taxes due.

Direct Indexing

Similar to owning an index fund or exchange traded fund (ETF), direct indexing strategies give investors exposure to a particular index. The most common being the S&P 500 Index.

Where direct indexing differs from simply buying an S&P 500 ETF (ticker: SPY as an example) can be summarized as follows:

- Direct indexing strategies are executed via a separately managed account (SMA) where the investor holds actual shares of the underlying companies rather than shares of an ETF representing said index. This enables the investor to see through to direct ownership and allows for customization of the holdings. For example, an investor could restrict the manager from holding tobacco stocks. The investor can also withdraw or add additional funds at any time, physical securities could be transferred in or out of the strategy, or they can choose to liquidate at any point.

- The manager of the SMA can buy and sell various positions as often as they’d like to take advantage of price deviations. This enables tax loss harvesting on each stock position rather than at the ETF level. The manager can be replacing Coca Cola with Pepsi and Exxon Mobil with Chevron on a constant basis to realize losses while maintaining exposure to a particular sector. The trades executed within the SMA tend to be done via electronic trading algorithms.

- A direct indexing strategy can be funded with cash, a single stock or a basket of stocks. The manager will work to transition an existing stock or basket of stocks to the desired benchmark by selling shares of the existing positions that funded the strategy. This typically generates realized gains if what funded the strategy had accumulated unrealized gains but the extent and timing of the transition can be managed strategically, within reason.

Over time, the direct indexing manager has two main objectives:

- To deliver the performance of the underlying index—S&P 500 Index in our example.

- To realize and harvest losses along the way.

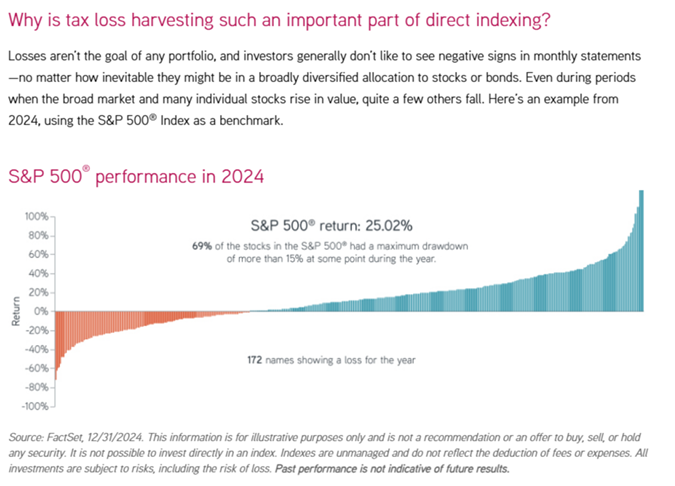

The graph below is from Parametric Portfolio Associates LLC, a leading direct index manager.

Source: Parametric Portfolio Blog post “Direct Indexing”

An investor in these strategies will be pleased if, over the long-term, they experienced a near identical performance as the S&P 500 Index but were able to harvest losses to help offset gains from other investments in their portfolio. Quarterly reporting from these managers presents both the performance of the strategy as well as accumulated losses realized to date specific to the investor.

Strategy in Practice: During a quarterly review with their advisor, a client is pleased that the direct indexing strategy was able to harvest $50,000 in losses while posting a positive return for the year. The client decides to sell some shares of their low basis concentrated stock position at a realized gain that equals the realized loss obtained by the direct indexing. They were able to diversify away some of the single stock risk away without incurring capital gains taxes.

Note: As the direct indexing strategy performs well over time, it may become increasingly difficult to keep “finding” losses to take. Over time, you may be holding a portfolio of ever-increasing unrealized gains. It may have been helpful to reduce the concentrated positions and diversify early in the process, but you may present yourself with the same issue of large unrealized gains to contend with down the road.

Long-Short Tax Harvesting

This approach has been described as “direct indexing on steroids”. Like direct indexing, managers of this type of strategy (typically hedge funds) have the objective of mirroring (or outperforming) index performance while realizing losses. However, they employ leverage (borrowing against your portfolio) and short selling (when an investors profits from price declines of a stock). The thinking here is that by adding leverage (borrowing money to allow for a much larger amount of assets and investments) and adding the ability to short sell (also a source for losses when stocks go up!) there is more opportunity to realize losses.

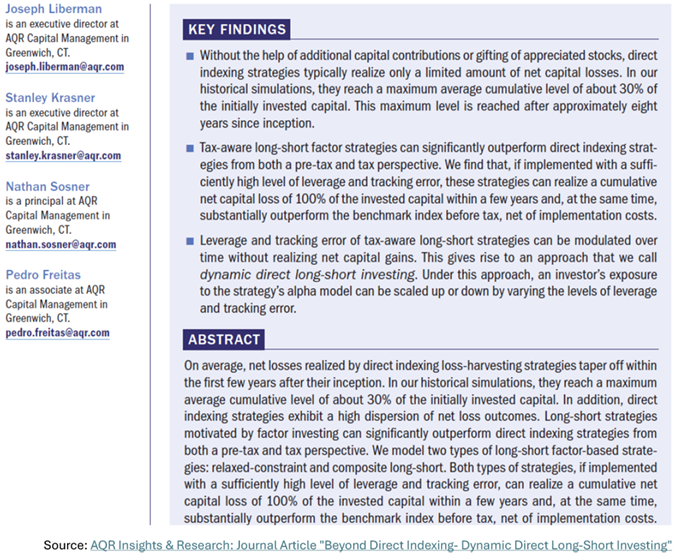

With these added “tools,” firms like Cliff Asness’ AQR Capital Management believe they can realize the losses you need to offset your concentrated position at a much faster pace than conventional direct indexing. The excerpt below is from an AQR article published in The Journal of Investment Strategies in 2023:

Source: AQR Insights & Research: Journal Article “Beyond Direct Indexing-Dynamic Direct Long-Short Investing”

It’s important to note that investors generally will fund this strategy with their concentrated stock, rather than cash. The hedge fund will borrow against the shares of your stock to fund the strategy.

While it might be true that by using additional tools you could arrive at your destination more quickly, these strategies are not a panacea. Disadvantages include:

- Leverage may increase risk of loss. There is also a cost to borrowing.

- Shorting stocks introduces added complexity so using an experienced manager is critical.

- Fees are higher than that of direct indexing.

- Your funds are generally locked up and cannot be withdrawn immediately.

- This strategy only recently was made widely available to the public so decades of historical performance is lacking.

- Minimums are typically north of $250,000 to $1,000,000 million depending on the manager.

Strategy in Practice: An investor with low-basis concentrated stock enters into an agreement with a hedge fund offering this type of strategy. The investor sends a predetermined quantity of its concentrated shares to fund the initial investment. About six months later, the investor receives a statement from the fund which shows that 25% of the concentrated stock has been liquidated on a tax neutral basis. The fund strategy generated enough losses to offset the realized gain on the 25% of shares sold. Investment returns were in line with expectations.

The investor is hopeful that this continues such that the concentrated stock is completely liquidated within the next two years and the investment strategy continues to perform in line with expectations.

Private Exchange Funds and 351 ETF Exchanges

If you don’t want to rely on harvesting losses or cannot stomach a hedge fund strategy that employs leverage and shorting stocks, you might consider two strategies that could help reduce your concentration risk and allow you to continue the tax deferral of your unrealized gains. Let’s introduce Private Exchange Funds and 351 ETF Exchanges to the mix.

Private Exchange Funds

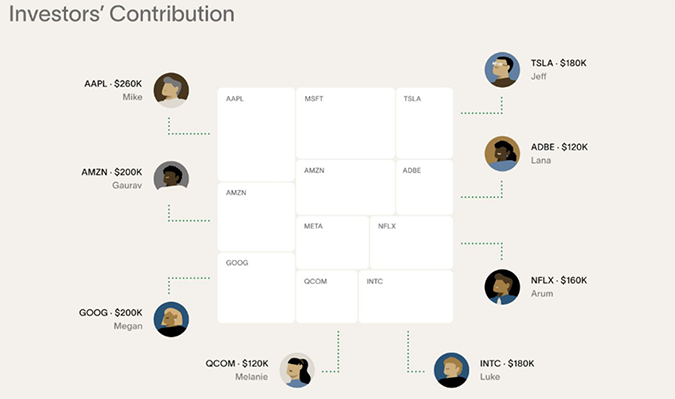

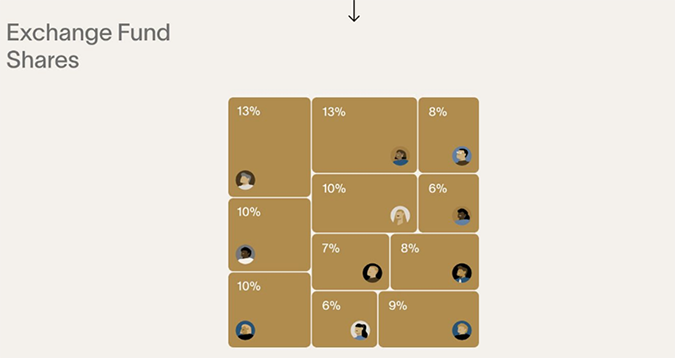

Codified by Section 351 of the IRS tax code in 1956, and available to accredited investors (What is an accredited investor? Definition from US S.E.C Government website), Private Exchange Funds allow you to contribute concentrated stock positions in exchange for shares of a diversified fund called an Exchange Fund.

The fund manager will establish an objective (to track the S&P 500 Index as an example) and open a fundraising period for investors to qualify and commit their shares of concentrated stock. The fund manager’s objective will be to construct the portfolio using my appreciated Apple shares, your appreciated Nvidia shares, your coworker’s appreciated Tesla shares and so on until they believe they have acquired a diversified pool of securities that will start to look like and track their benchmark index (again, the S&P 500 in this example). The following visualization from one of the main providers, Cache, should help explain:

Source: Cache.com- Exchange Funds

To qualify as an Exchange Fund, the IRS requires the manager to hold at least 20% of the fund in qualifying illiquid assets (think in terms of private real estate and/or commodities). The IRS also requires each investor to remain in the fund for seven years before they can withdraw their investment. Importantly, at the time of withdrawal, the investor will receive individual shares of the underlying holdings that the manager held at the expiration of the fund—not cash—and investors will maintain their original cost basis from seven years prior for tax purposes. Taxes aren’t eliminated, rather deferred as if you held onto your original concentrated stock for the seven-year period.

Exchange Funds are not only illiquid but generally charge higher fees. So, while they do offer you tax deferral and immediate diversification, it comes at a cost.

Strategy in Practice: An investor holds a significant amount of low-basis stock. They have no plans to use the funds but have grown anxious due to the high degree of concentration representing a large portion of their wealth. In exchange for immediate diversification, the investor is willing to contribute their shares to a Private Exchange Fund and wait out the seven years. The illiquid nature of the fund doesn’t bother the investor.

Once the seven-year lock-up is over, the investor will take possession of a basket of securities the manager holds at that time in proportion to the investor’s initial contribution. They can then determine the best course of action to deal with the deferred unrealized gains across a more diversified basket of stocks.

351 ETF Exchange

For investors seeking diversification away from concentrated positions while maintaining liquidity, a 351 ETF exchange may be a good fit.

This strategy, also named after Section 351 in the IRS tax code, utilizes the Exchange Traded Fund (ETF) structure to add liquidity to the Private Exchange Fund model. Providers of these 351 ETFs will seek to raise capital (stock contributions) prior to launch. As these ETFs become more popular, it’s possible for one or a few to launch each quarter.

When marketing their new 351 ETF exchange, the provider will establish their objective to attract potential investors. Two common strategies that have launched recently attempt to replicate the S&P 500 Index. One was on a market cap weighted basis (where the largest companies make up a greater share of the index) while the other was an equal weighted basis (where each company makes up the same percentage in the index).

The benefits of diversification and liquidity are attractive, but there is a catch. An investor cannot simply contribute one or two concentrated positions. In order to qualify for a 351 ETF Exchange, the IRS requires the following requirements:

- No single security can make up more than 25% of the total value of the contribution.

- The top five securities cannot exceed 50% of the total value of the contribution.

Diversification is key. A nice feature of this strategy is that existing ETF positions can be added to your contribution on a look-through basis. For instance, you can combine a portfolio made up of $800,000 worth of an S&P 500 ETF (ticker SPY as an example) and $200,000 worth of your concentrated stock. The combination should meet the diversification rules above as the IRS will consider the underlying holdings of SPY instead of the ETF itself wrapped as one security.

Ineligible holdings that cannot be contributed to a 351 ETF conversion include cryptocurrencies, mutual funds, private assets, restricted stock, options, or short positions.

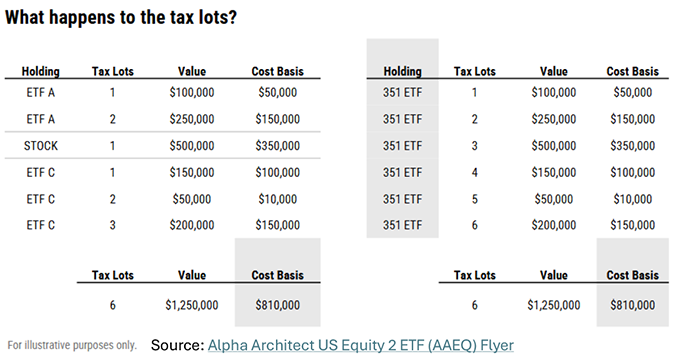

Look at the following example from another leading provider in the space called Alpha Architect. For reference, AAEQ is the ticker of the most recent 351 ETF Exchange product that they brought to market:

Source: Alpha Architect US Equity 2 ETF (AAEQ) Flyer

If executed properly, the 351 Exchange allows an investor to diversify away from their appreciated, concentrated positions without selling securities. The investor maintains their original cost basis, which is transferred from their prior individual holdings to an identical cost basis in the new shares of the 351 ETF.

The next chart from Alpha Architect depicts an example of how the cost basis transfers to the 351 ETF:

Once the new 351 ETF Exchange goes live, it is fully liquid. The investor can sell any amount of their shares of the new entity on the open markets. But recall, the investor’s tax basis did not change so realized capital gains taxes will be due.

The primary objective of this strategy is immediate diversification and liquidity. It does not eliminate the unrealized gains of your low-basis securities.

Strategy in Practice: You work for Nvidia and have acquired a large amount of company stock. You now own $1,000,000 worth of shares at a cost basis of $100,000. You still have confidence in Nvidia, but you are growing concerned that you are over-exposed to the company by both the value of stock you own and the fact that it is responsible for your paycheck. You seek to diversify without incurring a large tax bill from generating significant capital gains taxes.

Thankfully, you have been fortunate to build up a more diversified portfolio outside of your Nvidia shares but your holdings are also concentrated with a low cost basis. At present, the outside portfolio is made up of $500,000 worth of Apple, $500,000 worth of Microsoft as well as $3,000,000 in SPY. After a quick calculation confirms that you meet the diversification requirements, you decide to combine half of your Nvidia shares with the rest of the outside portfolio and take advantage of a newly formed 351ETF Exchange whose objective is to own an equal percentage of all S&P 500 Index stocks.

You have now gone from a very tech-heavy concentrated portfolio to a diversified portfolio without incurring any tax bill.

Once the new 351 ETF begins to trade on the stock exchange, you enjoy immediate diversification and access to liquidity.

Conclusion

In summary, investing with taxes in mind can add complexity to an already complicated practice—successful investing is difficult enough! However, with a bit of due diligence and the advice from qualified professionals like your CPA and investment advisor, strategies do exist to address these complexities.

So, if the content of this note piqued your interest, please do reach out to your CPA and investment advisor to see if any of these strategies may be useful to incorporate into your investment plan. Just like markets are dynamic and changing constantly, so too does the tax landscape. We encourage you to check in with your advisors from time to time to explore any updates and whether a new strategy is worth implementing.

Our team is also available should you like to discuss your personal financial picture in greater detail.

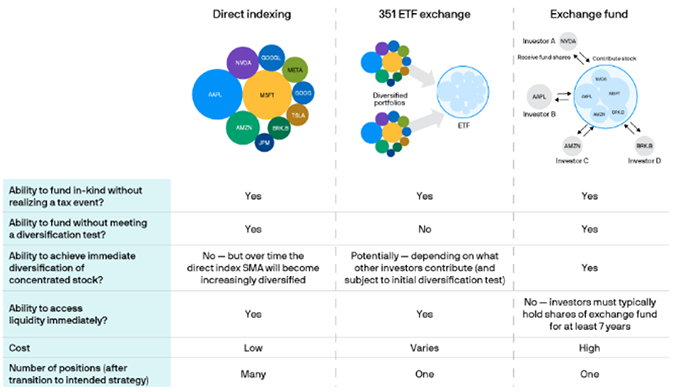

In the meantime, we leave you with the following infographic courtesy of JP Morgan that summarizes the differences between Direct Indexing, 351 ETF Exchanges and Private Exchange Funds:

Source: JP Morgan- Portfolio Insights- All Kinds of In-Kind

IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES

- Registration with the SEC should not be construed as an endorsement or an indicator of investment skill, acumen or experience.

- Investments in securities are not insured, protected or guaranteed and may result in loss of income and/or principal. Historical performance is not indicative of any specific investment or future results.

- Investment process, strategies, philosophies, portfolio composition and allocations, security selection criteria and other parameters are current as of the date indicated and are subject to change without prior notice.

- This communication is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services. Nothing in this communication is intended to be or should be construed as individualized investment advice. All content is of a general nature and solely for educational, informational and illustrative purposes.

- This communication may include opinions and forward-looking statements. All statements other than statements of historical fact are opinions and/or forward-looking statements (including words such as “believe,” “estimate,” “anticipate,” “may,” “will,” “should,” and “expect”). Although we believe that the beliefs and expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable, we can give no assurance that such beliefs and expectations will prove to be correct. Various factors could cause actual results or performance to differ materially from those discussed in such forward-looking statements. All expressions of opinion are subject to change. You are cautioned not to place undue reliance on these forward-looking statements. Any dated information is published as of its date only. Dated and forward-looking statements speak only as of the date on which they are made. We undertake no obligation to update publicly or revise any dated or forward-looking statements.

- Views regarding the economy, securities markets or other specialized areas, like all predictors of future events, cannot be guaranteed to be accurate and may result in economic loss of income and/or principal to the investor.

- Any references to outside data, opinions or content are listed for informational purposes only and have not been verified for accuracy by the Adviser. Third-party views, opinions or forecasts do not necessarily reflect those of the Adviser or its employees.

- Unless stated otherwise, any mention of specific securities or investments is for illustrative purposes only. Adviser’s clients may or may not hold the securities discussed in their portfolios. Adviser makes no representations that any of the securities discussed have been or will be profitable.

PDF Copy of Tax Strategies for Concentrated Positions